Mesopotamia as the cradle of civilisation

More than 6000 years ago, before the Greeks excelled in science and philosophy, civilisations were already flourishing in Mesopotamia – an area located between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, which flow down from the Taurus Mountains in Southern Turkey into the Persian Gulf. The climate of the region was semi-arid with a vast desert in the north, giving way to a 5800 square mile region of marshes, lagoons, mud flats and reed banks in the south. In ancient times, oak, pistachio, and ash forests covered the mountains and foothills with Alhagi maurorum (camelthorn) and Prosopis cineraria growing among them. Various reeds and the narrow-leaved cattail were abundant, and the giant mardi reed was used as a versatile construction material. The euphrates poplar (Populus euphratica) and a species of willow (Salix babylonica) grew in small belts beside the rivers and canals, the poplar providing strong timber for construction and boat building, as well as handles for tools. This region was rich in predatory wildlife with Asiatic lions (extinct in the region since 1918), sand cats, hyenas, panthers, owls, falcons, leopards, and crocodiles, while elephant, gazelles, giraffes, onagers (wild asses), wild boars, wild goats and roe deer grazed on the rich plant life. Bactrian camels and water buffaloes were domesticated to become beasts of burden.

The regular flooding of these two rivers made the land around them especially fertile and ideal for growing crops for food. Agriculture throughout the region was supplemented by nomadic pastoralism, where tent-dwelling nomads herded sheep and goats from the river pastures in the dry summer months, out into seasonal grazing lands on the desert fringe in the wet winter season. Mesopotamia has been called the fertile crescent and the “cradle of civilisation” because it is where settled farming first emerged as people started the process of clearance and modification of natural vegetation to grow newly domesticated plants as crops. Grain crops were barley, wheat, millet, and emmer (an ancestor of durum wheat). Other crops included sesame (Sesamum indicum), which was widely cultivated and used to make oil. Peas, figs, pomegranates, apples, and pistachio groves were also grown in this area. In the villages and cities of southern Mesopotamia, groves of date palms were common, often with vegetables such as onions, garlic, and cucumbers growing in the shade of the palm trees. The dates were eaten either fresh or dried, providing vital sugars and vitamins. Flax (Linum usitatissimum) was grown for its seeds, which can be ground into a meal or turned into linseed oil, while flax fibres taken from the stem of the plant are stronger than cotton and can be used to make linen cloth. In 1949, at the ancient Sumerian site of Nippur, a small clay tablet was discovered that after restoration and translation turned out to be a farmer’s almanac from around 3000 years ago. The tablet consists of a series of instructions for the purpose of guiding a farmer throughout their yearly agricultural activities and shows that they understood crop rotation and left fields fallow to maintain the fertility of the ground.

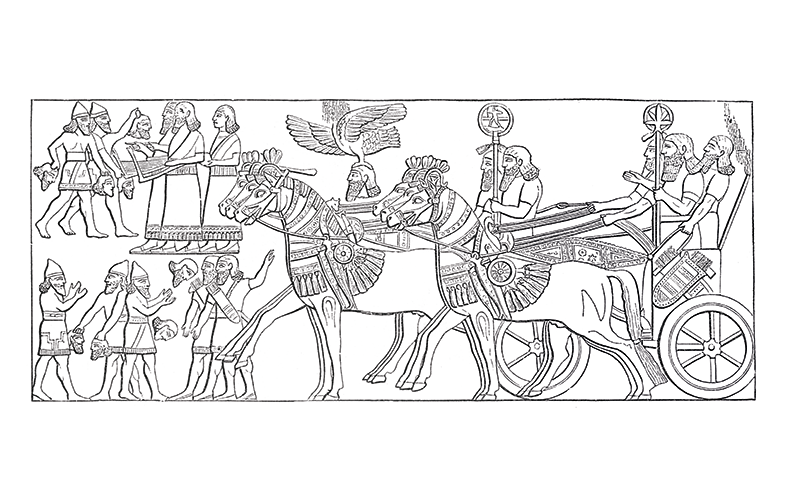

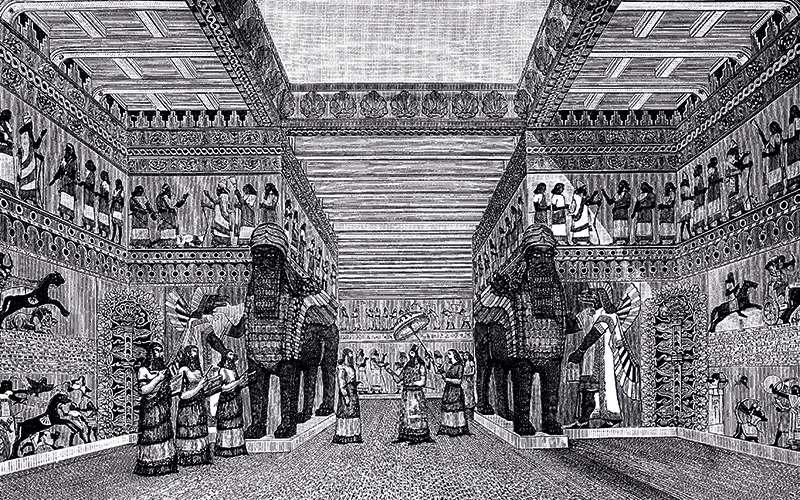

Mesopotamia was at the crossroads of the Egyptian and the Indus Valley civilisations and became a melting pot of languages and cultures that stimulated a lasting impact on writing, technology, language, trade, religion, and law. The Sumerian, Assyrian, Akkadian, and Babylonian civilisations established many cities during this time, and evidence shows extensive use of technology, literature, legal codes, philosophy, religion, and architecture in these societies. Uruk (250 km south of modern-day Baghdad), founded by King Enmerkar, around 4500 BC, is widely regarded as the world’s first city and was the birthplace of writing (around 3200 BC), but it was also renowned for its architecture and other cultural innovations. One of the city’s most famous kings was Gilgamesh, who coveted immortality following the death of his friend Enikdu (which all Star Trek fans will know was the tale recounted by Captain Picard in the 102nd episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation “Darmok”).

Medicine and magic

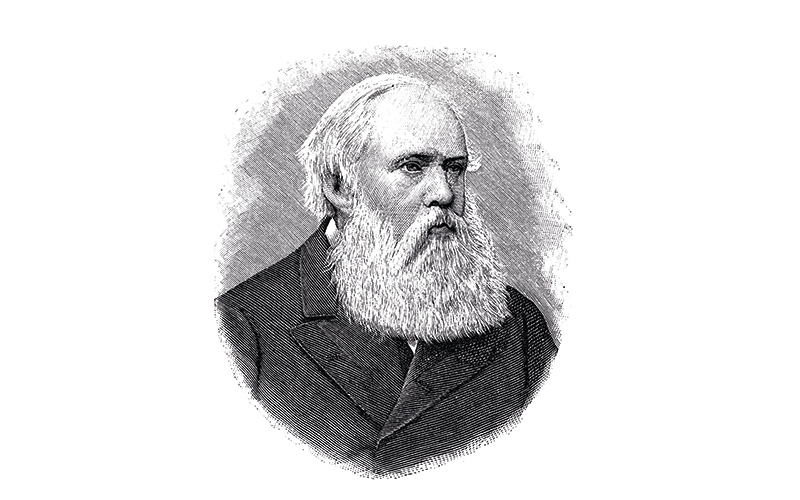

When King Ashurbanapal of Assyria’s library of clay tablets was discovered by Sir Austen Henry Layard and deciphered in the late 19th century, they transformed the understanding of Mesopotamian history from the earliest human occupation in the Palaeolithic period up to late antiquity. This history was pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and after the introduction of writing an increasing number of historical sources. There have been almost a thousand clay tablets and scripts found, including hundreds of medical texts. Some describe how to make poultices, enemas, suppositories, pills and infusions. The ingredients, which included mustard, fig, myrrh, bat droppings, turtle shell powder, river silt, and snakeskin, were dissolved in wine, milk and beer prior to administrating to the patient. The Sakikku, or “All Diseases”, was a late Babylonian diagnostic manual consisting of 40 clay tablets, which included a treatise on the diagnosis of epilepsy or “the falling disease.” The writer explains the subtleties of the neurological disease’s presentation in detail, provides basic prognoses, and ascribes different kinds of seizures to malevolent spirits. “If the epilepsy demon falls upon him and on a given day, he seven times pursues him—then he has been touched by the hand of the departed spirit of a murderer. Then he will die.”

But the Mesopotamian physicians did try to treat or manage epilepsy patients by prescribing fish oil and an extract of cedar (Pinus cedrus or Cedrus libani), although current studies seem to suggest that cedar contains thujone, 1,8-cineole, camphor, or pinocamphone, which have been identified as pro-convulsive agents and may actually trigger seizures. All of this was more than a thousand years prior to the lifetime and teachings of the father of Western medicine, Hippocrates. Clay tablets show that medicine in Mesopotamia was a well-established profession that included diagnosis, pharmaceutical applications, and the treatment of wounds. In line with the strong theocratic state culture, healers were closely integrated with the powerful priestly fraternity, and were essentially divided into three specialities: barû (seers) who were experts in divination, âshipu (exorcists), and asû (healing priests) who tended directly to the sick.

Using a human guinea pig before administering a medical prescription to the royal patient was suggested

A barû began the divination ceremony by first addressing the oracle gods, Šamaš (the Sun-God) and Adad (the Storm-God), with prayers and benedictions, requesting them to “write” their message upon the entrails of a sacrificial animal, or barûtu. Records suggest that King Sennacherib (approximately 740–680 BC) was not always convinced that answers to important questions by the barû were the result of separate divinations but more of a collusion to deliver the results that he wanted to hear! Meanwhile the ašipu did a meticulous examination of the patient’s body and of the environmental circumstances relevant to the patient’s illness. The ašipu was a mediator to the gods able to deal with the evil and supernatural powers. Finally, the asû, described by contemporary texts that detail them as a scientific physician, carried out empirical practice by prescribing remedies containing mixtures of organic and inorganic substances like a plant, an animal, or a mineral in the form of an amulet. They treated wounds and injuries, dealt with broken bones, and gave antidotes. Nevertheless, patients had a choice to visit any of the healers. Consultations between them appeared to be common and contemporary records show that in 1280 BC, the Hittite monarch Hattusilli III asked the Babylonian king to send both an asû and an ašipu to his court, in order to treat him. It should be noted, however, that not all medical procedures were taken at face value. A letter written by King Esarhaddon’s barû Adad-šuma-usur suggested using a human guinea pig before administering a medical prescription to the royal patient. It is unlikely that the chosen “volunteer” suffered from the same ailment as the patient, so the drug was probably not being tested for its medicinal efficacy but probably that it showed no adverse effects. In the epic of Gilgamesh, the king hears of the existence of a miraculous plant to help him in his quest for immortality. Gilgamesh finds the plant, in a subterranean or underwater cave believed to be off the coast of Bahrain and wants to test this mysterious plant on an old man before eating it himself. Luckily for the old man a serpent steals the plant, and Gilgamesh returns home to the city of Uruk, having abandoned hope of immortality or renewed youth.

Herbal medicine

Plants were the main source for curing and alleviating diseases in ancient Mesopotamia with Sumerian clay tablets dating from the 3rd millennium BC mentioning various medicinal plants. King Merodach-Baladan II (722–710 BC) of Babylonia grew many spices and herbs (cardamom, coriander, garlic, thyme, saffron and turmeric) in medicinal gardens and more exotic plants were often imported from other lands, or sent as tributes and gifts and occasionally as spoils of war. King Tiglath-Pileser I (1114–1076 BC) ordered entire plants and trees to be collected from lands he conquered to be replanted in his own medicinal garden in Assyria. Garlic as a drink or a tonic with tea or wine was mentioned in a document written by the Sumerians around 3000 BC. They used to eat garlic, but it was also their medicine for infectious fevers as well as for treating diarrhoea. Even garlic teas were used externally to treat sprains, strains and any painful swellings. Interestingly, sometimes certain plants were to be avoided in certain circumstances; for diseases of the heart the patient was told to

avoid turnips, while patients with eye conditions were to avoid leeks and coriander. It should be noted that Dafni (2019) and Rumor (2021) found that it was difficult to translate some of the more exotic plants into their modern-day equivalents, so quite often there is simply a generic term for the plant being used in the remedy. Less frequently, other materials were used alongside the healing plants, such as stones and minerals or various animal products. Liquid or semi-liquid carrier substances were used for administering medicaments (water, milk, vegetable juices, alcoholic drinks, syrup and honey). Therapeutic texts detail the two main ways in which medicine could be applied, externally as bandages, salves and healing baths, or taken internally in the form of healing potions, tampons, and suppositories.

Sometimes medications were used simultaneously to treat a certain medical condition. One cited passage shows how several healing procedures occur alongside each other as complementary ways of treating a single medical condition: “If a man has cramps, his stomach does not retain food and drink, he brings it back through the mouth and he has vomiting spells, to cure him mix one half of a measure of dates, one half of a measure of cassia (Cinnamomum cassia), and add mint, and let him drink it fasting. Also prepare an enema of oil and introduce it into the anus, then his stomach will again retain food and drink, and he will recover.”

Other afflictions of the gastro-intestinal tract, such as flatulence or haemorrhoids, were treated with suppositories made from finely ground plants such as oak galls (Quercus infectoria), myrrh (Commiphora myrrha) and crushed alum mixed with suet or occasionally wax and “inserted” into the affected region.

There are many instances of directions to mix drugs into a paste, or a salve to be smeared on a cloth or on a bit of leather, and to be applied to some part of the body. A typical prescription for a head compress states: “If a man has a burning headache affecting his eyes, which are bloodshot, take one-third of a measure of sikhlu (a thorny weed), crushed and powdered, and knead with cassia juice, wrap it around his head, attach it (with a bandage), and do not remove for three days.”

If that failed to cure the symptoms the asû, the second line of healing, was sacrificing a bird and mixing some of its body parts in a resin of a plant. This mixture was then magically enriched with an incantation: “You slaughter a captured goose. You take its blood, its throat, its gullet, its fat, the rind of its gizzard. You char (them) over charcoal. You mix (them) within cedar ‘blood’, and then three times recite the incantation ‘Evil Finger of Mankind’. You repeatedly anoint his head, his hands and everything that affects him and he shall get better. The ‘headache’ will be eradicated.” This would probably involve the services of an ašipu for the incantation.

The second line of healing was sacrificing a bird and mixing some of its body parts in a resin

Another patient consumed a healing potion made from two different healing plants (asafoetida and tiyatu) mixed with beer. This refreshing potion was followed by an enema, which was boiled down šammu pesû (“white plant”) in oil, to reach the affected part from a different direction. Then, the patient was washed with water containing leaves from various plants, the aim of which was presumably to clean their body and remove all expelled bodily fluid. A second enema made from the juice of šunû (“chaste tree”) and kasû (“tamarind”) was then prescribed. Finally, a salve was made from boiled down burašu (a kind of juniper) and kukru (an aromatic plant), smeared onto a bandage and wrapped around the patient. Bandages were also important in treating eye diseases, but it seems that daubing a salve onto the eye or dripping and blowing healing substances directly into the eyes with the help of a bronze tube or a reed straw were preferred, although seeing the ingredients for the salve might make you blink – a mixture of bat guano, a white plant and salt in syrup and oil (not something you would find in your local pharmacy). This mixture was probably slightly better than one used for a toothache, where a type of lizard (a humbabitu) was crushed into a paste wrapped in a tuft of wool, sprinkled with oil and placed inside the sick tooth. Then a paste of black cumin (“zibu”) and ata’išu (a plant) was smeared over the tooth. For impotency, the blood of a bat was diluted with stagnant water and then mixed with various herbs (hopefully to improve the taste) was prescribed.

They were also aware of the use of narcotic substances. These were derived from Cannabis sativa (hemp), Mandragora spp. (mandrake), Lolium temulentum (darnel), and Papaver somniferum (opium).

Aftermath

Civilisations rise and they fall; certainly the empires in Mesopotamia were no exception. Records suggest that although there was much infighting between the various tribes to gain control, fossil samples have been found that show that there was also a prolonged winter season accompanied by unusually strong northeasterly winds (the shamal) and a drought. This may have caused a climate shift unleashing devastating dust storms across the region resulting in an inability to grow crops causing famine and mass social upheaval. But in 539 BC the Neo-Babylonian Empire that was controlling Mesopotamia was overthrown by a bigger threat – the Persian Empire.

The Sumarians, Babylonians and Assyrians have left us with a rich legacy of art, philosophy, medicine and law. These were progressive, educated, and forward-thinking people. In 1901 a stone pillar of cuneiform script was discovered that was to become one of the longest, best-organised, and best-preserved legal texts ever found. This basalt stele was commissioned by King Hammurabi of Babylon (1810–1750 BC) and was written in 1755–1750 BC. There are passages on commerce, common assault, rates of hire and agriculture. It also included several pronouncements on medical care, which held physicians responsible both for success and failure. The Mesopotamian medical observations on the symptoms, diagnosis and prognosis of the most common diseases were collected into tablets like the Sakikku (Diseases Handbook) and the Assyrian Herbal and Prescription Texts, which are still identifiable to the present day.

Dr Stephen Mortlock is semi-retired and working as a locum Biomedical Scientist at Frimley Park Hospital in Surrey. Stephen would like to thank Marcial Navarro and all the microbiology staff for their continued support and training.

To see this article with full references, visit thebiomedicalscientist.net